Scattering

🎯 Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, you should be able to:

- Explain the fundamental concepts of acoustic scattering and diffusion.

- Derive the scattering cross section for spheres and other canonical shapes.

- Compute scattered pressure and particle velocity fields.

- Understand surface scattering, including rough, corrugated, and diffusive surfaces.

- Model directionry toal scattering patterns, including Lambertian distributions.

- Apply scattering theo architectural acoustics, transducer design, and environmental noise control.

- Analyze frequency-dependent scattering behavior and the role of wavelength-to-object-size ratio.

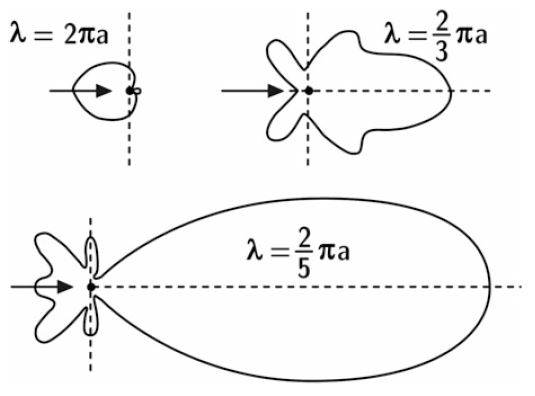

Sound waves may encounter obstacles of varying sizes and shapes. The scattered field depends strongly on the size of the object relative to the wavelength, its geometry, and the material properties.

- Forward scattering dominates when objects are large compared to wavelength.

- Backscattering corresponds to reflection-like behavior.

- Oblique scattering can redistribute energy in all directions.

Exact solutions exist only for simple geometries like spheres, cylinders, and planar surfaces. More complex objects require numerical methods (BEM, FEM) or approximate models.

Figure. Sound scattering at a sphere with radius

Object Scattering

To handle scattering in practice, the scattered field is often approximated by an equivalent spherical scatterer. This leads to the scattering cross section, which quantifies the effective area that intercepts the incident energy.

For a plane wave of intensity , the scattering cross section is:

where is the power radiated by the scatterer.

The total acoustic field combines the incident and scattered components:

and the corresponding particle velocity normal to the surface:

Note: The scattered pressure is generally direction-dependent, leading to anisotropic energy distribution.

Frequency Dependence

- For low frequencies (wavelength > object size), the scattering is nearly isotropic (Rayleigh scattering).

- For high frequencies (wavelength < object size), specular reflection dominates in the forward direction, with diffracted waves around edges.

Animated Examples

Scattering of a Plane Wave from a Rigid Sphere and an Infinite Rigid Cylinder

Figure. Scattering patterns of rigid objects: sphere vs cylinder

Scattering of a Plane Wave from a Rigid Sphere and a Pressure Release Sphere

Figure. Comparison between rigid and pressure-release spheres

Pressure-release spheres create phase-inverted scattered waves, reducing forward scattering intensity and demonstrating the effect of boundary conditions.

Surface Scattering

Scattering also occurs from rough or corrugated walls. The incident plane wave interacts with each surface element (Huygens sources), producing a complex interference pattern.

Figure. Scattering from a rough surface

Roughness and Frequency Effects

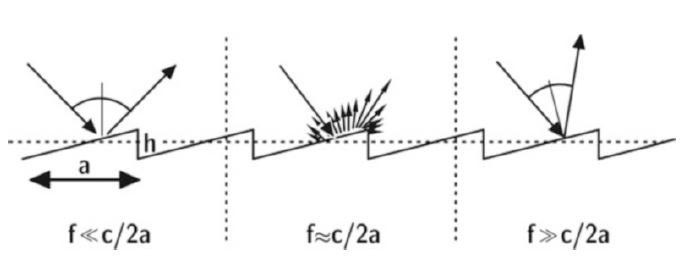

- If corrugation *depth and length , the wall behaves effectively smooth.

- If , , the scattered field becomes highly directional with lobes in non-specular directions.

- At high frequencies, fine structures produce specular reflection, while low frequencies produce diffuse scattering.

Figure. Scattering caused by surface corrugations

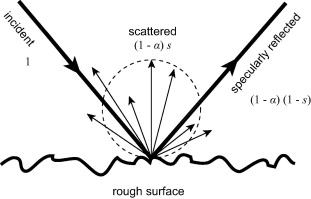

Energetic Formulation

The total energy of reflected sound is split into specular and scattered portions:

where:

- = scattered energy fraction

- = absorption coefficient

- = specularly reflected energy

From this, the scattered fraction is:

Figure. Energy reflected from a corrugated surface: scattered vs specular

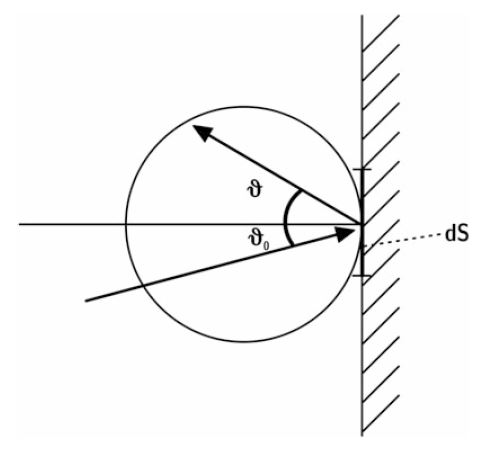

Directional Distribution and Diffusion

The diffusion coefficient describes uniformity of scattered sound:

- 1 → energy evenly scattered in all directions

- 0 → energy concentrated in one direction

The Lambertian scatterer obeys cosine law:

Where:

- = irradiation strength

- = wall element area

- = absorbed fraction

- = scattering angle

Example: moon surface, diffusive ceilings, or white paper appear uniformly bright independent of observation angle.

Figure. Probability distribution of scattered sound (Lambert’s law)

- Wave decomposition: Scattered fields can be decomposed into zero-order (specular) and higher-order lobes.

- Frequency-dependent behavior: At low frequencies, scattering is isotropic; at high frequencies, directional lobes appear.

- Material effects: Boundary type (rigid, soft, pressure-release) modifies the phase and amplitude of scattered waves.

- Huygens principle: Surface scattering can be viewed as a superposition of secondary wavelets, forming complex interference patterns.

- Diffuse reflection: Important for room acoustics, concert hall design, and noise control.

📝 Key Takeaways

- Acoustic scattering occurs when sound waves encounter obstacles or rough surfaces, redistributing energy in various directions.

- The scattering cross section quantifies the effective area of an object that interacts with incident sound, linking scattered power to incident intensity.

- Total acoustic field combines the incident wave and the scattered wave: .

- Surface scattering depends on the relative size of corrugations or roughness to wavelength; low frequencies see smooth-wall behavior, high frequencies produce directional lobes.

- Specular vs diffuse scattering: Zero-order lobes correspond to specular reflection, while higher-order lobes distribute energy in non-specular directions.

- The diffusion coefficient quantifies uniformity of directional scattering (1 = fully diffuse, 0 = highly directional).

- Lambert scattering obeys the cosine law, producing a uniform intensity on a detector independent of observation angle.

- Boundary conditions (rigid, soft, pressure-release) influence both the phase and amplitude of scattered waves.

- Huygens principle allows modeling complex surfaces as arrays of secondary sources producing interference patterns.

🧠 Quick Quiz

1) Which parameter quantifies the effective area of an object that scatters incident sound?

2) The total acoustic field in the presence of a scatterer is expressed as:

3) What is the significance of the diffusion coefficient in surface scattering?

4) According to Lambert’s cosine law, the intensity of scattered sound from a wall element is:

5) How does the frequency of sound relative to object size affect scattering?