Diffraction

🎯 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the phenomenon of diffraction and identify its physical causes.

- Apply Huygens–Fresnel and Biot-Tolstoy-Medwin principles to model diffracted fields.

- Calculate diffraction effects in simple geometries (edges, slits, cylinders, spheres).

- Understand frequency dependence and shadow region formation.

- Apply practical models such as Maekawa’s and UTD for engineering problems.

- Integrate diffraction effects in room acoustics, noise barriers, and urban sound propagation models.

Introduction to Diffraction:

Diffraction occurs when a sound wave encounters an obstacle with a free edge, corners, or boundaries between materials with differing impedances. The diffracted wave appears to be radiated from the edges or perimeters of these obstacles.

- If the obstacle is small compared with the wavelength, the incident wave remains largely unaffected.

- As the obstacle size increases relative to the wavelength, a shadow region appears, becoming sharper as the diffraction effect grows. This shadow is a result of interference between the incident wave and the diffracted wave, leading to partial or total cancellation.

Diffraction is not merely an academic curiosity; it influences:

- Binaural hearing and sound localization.

- Transmission of sound through doors or windows with small gaps.

- Orchestra sound projection from pits in opera houses or concert halls.

Historical and Theoretical Foundation:

The mathematical description of diffraction dates back centuries:

- Huygens (1690) proposed that every point on a wavefront acts as a secondary source, radiating spherical wavelets.

- Fresnel (1815–1821) expanded this concept to include superposition and interference of wavelets, yielding diffraction patterns.

- Kirchhoff formulated diffraction integrals for apertures and obstacles, extending Huygens–Fresnel principles.

- Sommerfeld (1896) addressed diffraction around obstacles comparable to the wavelength, providing a wave-theoretic approach.

- Keller (1962) formulated the Geometrical Theory of Diffraction (GTD), linking diffraction to ray splitting at edges.

- Biot and Tolstoy (1957) developed a frequency-dependent transfer path model, describing diffraction in closed form.

- Medwin (1981) refined this into the Biot-Tolstoy-Medwin (BTM) approach, enabling accurate calculations for finite-sized obstacles.

The BTM method allowed closed-form evaluation of diffraction around finite screens, edges, and barriers, paving the way for engineering applications.

Practical Diffraction Models:

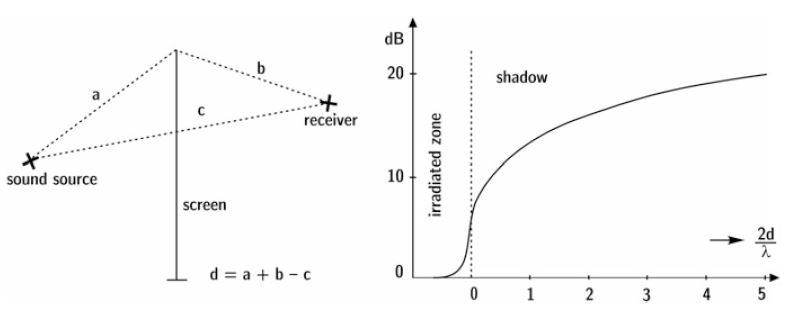

Maekawa’s Model (1968)

- Maekawa conducted experimental studies on diffraction by an infinite half-plane, measuring sound reduction as a function of frequency and geometry.

- The model computes the detour distance of the wave around a vertical screen to the receiver.

- Insertion loss approximation:

- Widely used in urban noise propagation and open-plan office acoustics.

- Forms the basis for ISO 9613-2 standard calculations.

Figure. Estimating the insertion loss of a screen

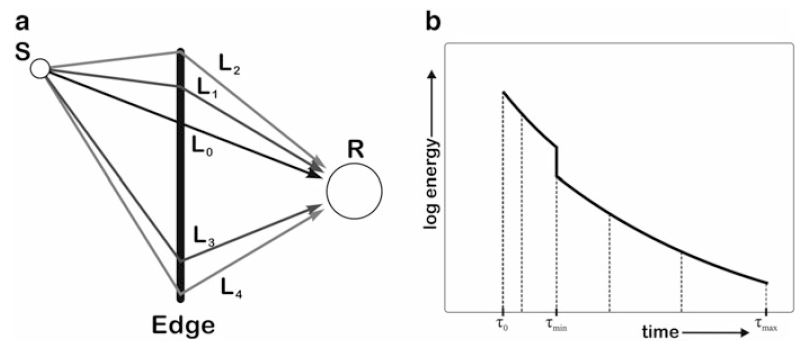

Unified Theory of Diffraction (UTD)

- UTD extends GTD by treating edges as lines of secondary point sources, integrating contributions along the edge line.

- Based on Biot-Tolstoy-Medwin but adapted for finite edges, producing time-discrete impulse responses.

- Key features:

- Accounts for multiple paths over the edge.

- Computes energy and delay of each diffracted path.

- Supports continuous, decaying impulse response for practical simulation.

Figure. (a) Sound paths from to via an edge. describes the shortest path over the edge, the other paths have longer detours over the edge. (b) Energetic edge diffraction impulse response. is the delay of the shortest path, and describe the delays over the edge’s starting point and end point

Mathematical Description:

For a single edge or slit in an infinite screen, diffraction can be described by Huygens-Fresnel integral:

Where:

- is the amplitude contribution from each secondary source along the edge.

- is the distance from the secondary source to the observation point "

- The integral sums contributions along the edge line.

For finite edges, time-discrete impulse response accounts for detours and phase delays:

Where:

- is the amplitude along path over the edge.

- is the travel time along that path.

Frequency and Geometrical dependence:

- Low-frequency waves obstacle size: strong diffraction, shadow region blurred.

- High-frequency waves obstacle size: sharper shadow, weaker bending.

- Diffraction effects are pronounced for apertures and gaps comparable to the wavelength.

Practical engineering: frequency-dependent diffraction coefficients are used in simulations of noise barriers, urban sound propagation, and room acoustics.

Applications in Acoustics:

- Noise Barriers: insertion loss estimation using Maekawa’s model.

- Architectural Acoustics: sound propagation from orchestra pits or around columns.

- Urban Planning: modeling sound detours over buildings, edges, and fences.

- Transmission through small openings: doors, windows, and ventilation.

Animated Examples: Animation of Diffraction over a Barrier

Barrier Height

Barrier Height

Barrier Height

🧪 Interactive Examples

📝 Key Takeaways

- Diffraction is the bending of sound waves around obstacles or through apertures.

- The intensity and sharpness of diffraction effects depend on the ratio of wavelength to obstacle size.

- Huygens, Fresnel, Kirchhoff, Biot-Tolstoy, and Medwin laid the foundation for modern diffraction theory.

- Maekawa’s model provides a practical method for estimating insertion loss behind screens and barriers.

- The Unified Theory of Diffraction (UTD) generalizes edge diffraction using secondary sources along finite edges.

- Frequency-dependent diffraction modeling is essential in architectural acoustics, urban noise prediction, and transmission through openings.

🧠 Quick Quiz

1) Diffraction becomes significant when:

2) The shadow region behind a diffracting object occurs because:

3) The Unified Theory of Diffraction (UTD) models diffraction by treating edges as:

4) Maekawa’s diffraction model estimates the insertion loss of a screen using the detour . Which formula expresses this approximately?

5) In practical acoustics, diffraction affects: